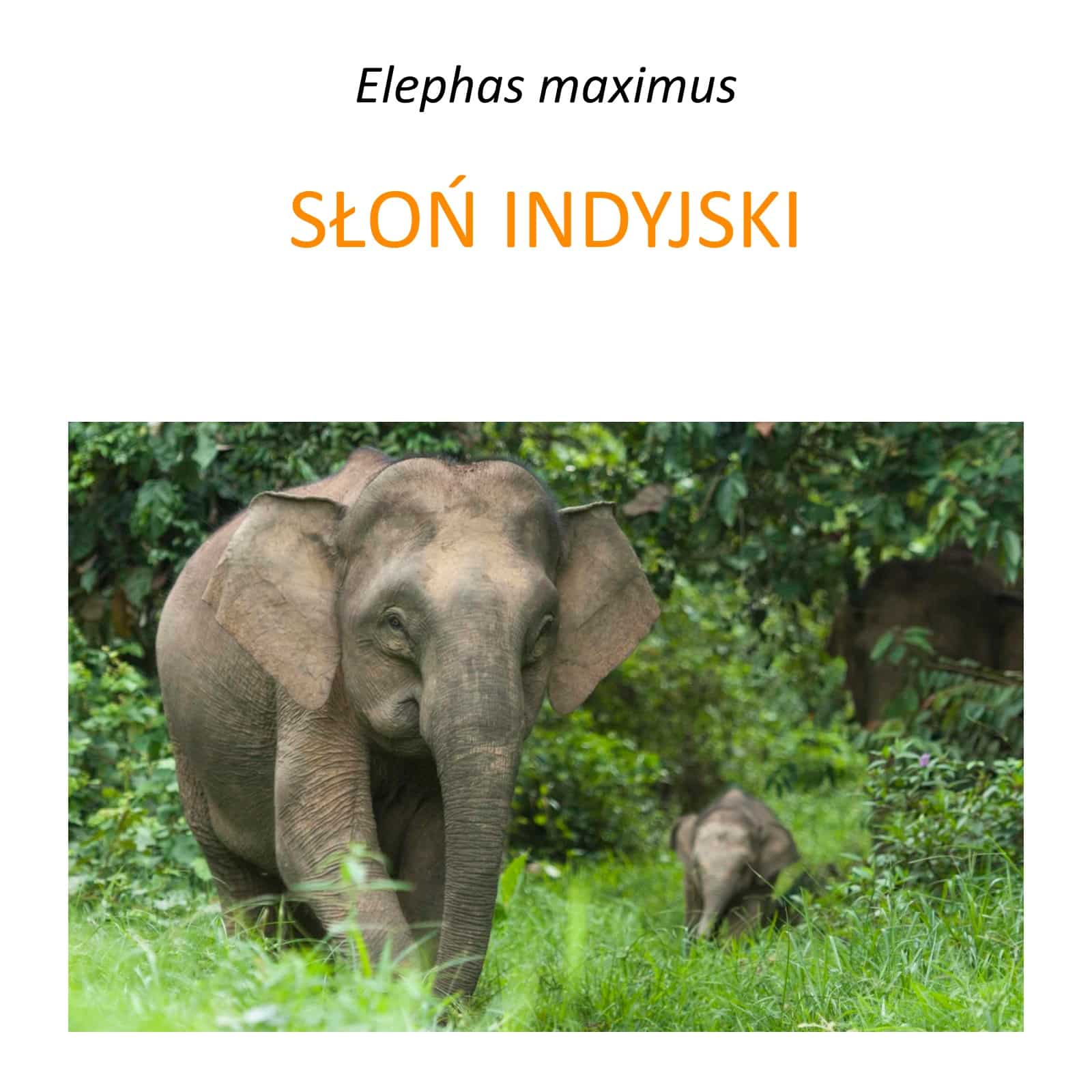

Description

Elephants are the largest living land animals in Asia. They are generalists, inhabiting a wide range of environments, from dry thorn forests to rainforests, and can survive by utilizing highly diverse resources. Their long-standing relationship with humans has made them cultural icons. Today, fewer than 50,000 Indian elephants remain in the wild, and they are classified as Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Although the taxonomy of Indian elephant (Elephas maximus) subspecies has varied depending on the author, the latest classification by Shoshani and Eisenberg (1982) recognizes three subspecies: the Bengal elephant (E. m. indicus) on the Asian continent, the Sri Lankan elephant (E. m. maximus) on Sri Lanka, and the Sumatran elephant (E. m. sumatranus) on the Indonesian island of Sumatra.

Due to their large habitat requirements, elephants are considered “umbrella species”, meaning their conservation also protects many other species sharing the same environment. They can also be classified as “flagship species” due to their cultural and symbolic value, as well as “keystone species” because of their critical ecological role and impact on the ecosystem.

Indian elephants once ranged from Western Asia, nearly reaching the Mediterranean coast, across the Indian subcontinent, and eastward into Southeast Asia, including the islands of Sumatra, Java, and Borneo. Their range extended north to the Yangtze River in China. This historical distribution covered over 9 million km².

Today, the species has lost about 95% of its historical range and is now extinct in Western Asia, Java, and almost all of China.

Currently, Indian elephants are found in 13 countries, occupying a total area of 486,800 km². The species occurs in Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, and Sri Lanka in South Asia, as well as in Cambodia, China, Indonesia (Kalimantan and Sumatra), Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, and Malaysia (the Malay Peninsula and Borneo).

The elephants of Borneo have traditionally been classified as Elephas maximus indicus (Shoshani & Eisenberg, 1982) or Elephas maximus sumatranus (Medway, 1977). However, Bornean elephants differ both morphologically and behaviorally from elephants in mainland Asia (Cranbrook et al., 2008).

Mitochondrial DNA haplotype analysis (Fernando et al., 2003; Sharma et al., 2018) also confirms these differences, indicating that Bornean elephants are genetically distinct from all South and Southeast Asian elephant populations and may have been isolated for over 300,000 years.

The final subspecies classification is pending further detailed morphometric and genetic studies across the species’ entire range. These studies may lead to the recognition of a separate subspecies—Elephas maximus borneensis.

The Indian elephant is one of the few remaining megaherbivores (i.e., plant-eating mammals weighing over 1,000 kg) still living on Earth. As hindgut fermenters, with relatively low digestive efficiency, elephants must consume large quantities of food daily to meet their energy requirements. They are generalists, feeding on a variety of plant species that change depending on habitat and season. Elephants travel long distances in search of food and shelter. They can spend 14–19 hours a day foraging, during which they may consume up to 150 kg of fresh plant material.

The lifespan of Indian elephants ranges from 60 to 70 years. Males reach sexual maturity between 10 and 15 years of age, while females can reproduce as early as 11 years old. Due to their long gestation period (approximately 21 months) and the extended nursing phase (8–10 months, sometimes up to a year), the minimum interval between births is around 4–5 years.

Indian elephant society is structured into well-defined, matriarchal herds or clans, consisting of adult females, as well as juvenile and young male and female elephants. Juvenile males eventually leave their natal clans, while adult males (bulls) are mostly solitary, though they may form loose social bonds with other males and temporarily join female groups during the breeding season.

Threats

Habitat loss and fragmentation – Driven by economic growth and a growing human population, elephants in Asia compete for space on the world’s most densely populated continent, where the human population growth rate ranges from 0.5% to 1.5% per year. The expansion of human settlements, plantations, industries, agriculture, mining, and linear infrastructure (roads, railways, irrigation canals, power lines, pipelines) has forced elephant populations into smaller and more isolated forest areas, often surrounded by human communities, which block their traditional migration routes.

Extinction of small populations – As elephant populations become increasingly confined due to habitat loss and fragmentation, their chances of survival decrease in the face of environmental disasters (such as droughts and floods), disease outbreaks, or random threats (such as severe disruptions in sex ratios).

Human-elephant conflict – The increasing loss and fragmentation of habitat also lead to human-elephant conflict, another critical threat across the species’ range. Since a large portion of elephant habitat lies outside protected areas, overlapping with agricultural lands and human settlements, elephants and people frequently come into conflict, often with negative consequences. Each year, elephants cause millions of dollars in crop damage, while hundreds of humans and elephants are injured or killed in these conflicts. In retaliation, villagers poison or electrocute elephants. These conflicts result in over 600 human deaths and 450 elephant deaths annually in Asia. Beyond direct retaliation, elephants are also killed due to infrastructure-related causes, including Train collisions (mainly in India and Sri Lanka), Vehicle collisions (mainly in Malaysia and Thailand).

Poaching and illegal trade – Poaching remains a significant threat in Asia, particularly due to the growing demand for elephant skin products. In Southeast Asia, there is a well-established black market for products made from elephant tusks, trunks, meat, skin, tails, and hair. Given the already small and highly fragmented populations of elephants in many of these countries, poaching poses a severe risk to their survival. Additionally, the capture of elephant calves and young individuals for the live animal trade remains a serious threat in some parts of their range.

What Are We Doing?

We support elephant conservation in Borneo by providing financial assistance to the wildlife monitoring program on oil palm plantations, led by Hutan. Data collected from camera trap systems show that creating ecological corridors between plantations—especially along animal migration routes to rivers—is crucial for wildlife movement. These cameras not only capture elephants but also Sunda clouded leopards, sun bears, orangutans, and proboscis monkeys!

This program serves two key purposes:

- Understanding the region’s biodiversity through scientific monitoring.

- Educating plantation owners about how reforestation helps protect their crops from wildlife damage.

Animals prefer moving through forested corridors rather than crossing cultivated lands, making habitat connectivity essential for both conservation and human-wildlife coexistence.

In 2001, in response to repeated complaints from villagers about human-elephant conflicts, Hutan established the “Elephant Conservation Unit”.

The team collaborates with plantation owners to chase elephants away from their properties using non-lethal deterrents, such as cannon blasts, spotlights, and other peaceful methods to drive the animals away from cultivated areas.

Additionally, electric fences have been installed to protect plantations and cemeteries from elephant intrusions.

These short-term measures must be combined with long-term, sustainable solutions to improve the policy framework for elephant population management across their range. Hutan has therefore engaged in research to better understand the root causes of human-elephant conflicts and explore how elephants can coexist within human-altered landscapes.

Efforts have been made to build capacity and raise awareness, showing local communities that it is possible to share the environment with these large neighbors. The team is now increasingly involved with local communities, where elephant-related damages have risen in recent years. In response, “Elephant Guardian Units” have been trained in five additional villages to monitor elephant movements and mitigate the impact of their presence.